Excerpt: Munchies

by Teresa Finney

The gold masa sticks to my palms like wet sand. In addition to staining my clothes, the dough is littered all over my grandparents’ kitchen table On the stove, large pots of diced beef and pork, seasoned with oregano and cumin, have been simmering since the earliest hour of morning. It is Christmas Eve and per tradition, my family is making tamales. I am 13 years old and not interested.

I have been assigned the job of masa spreader, my least favorite. I’m not good at it and I know this because each time I set one corn husk down on the table, either my mom or grandma will pick it back up and thin out the masa, effectively showing me how it’s done. The corn husks have been soaking overnight in water to soften. The masa, which has been purchased from the Mexican grocery store, the one with the tamarindo candies my teenage self can’t imagine taste any good (she was wrong), has been mixed with a spicy mole rojo by hand.

My real job on Christmas Eve—the only one I feel any good at—is to be an observer.

I notice my grandma in her masa-stained apron taste-testing the meat and rolling her eyes at my grandpa—a Guadalajara-born immigrant with a lion-like voice, even when not yelling—and then asking him to make another round of Mudslides. I see my aunts carefully assembling tamales, although they do it with the expected grace and ease of women who’ve been making them for years. My cousins are watching television in the living room with my uncles, all of whom are either tipsy, drunk, or getting there. By the time 8 PM rolls around, the tamales are usually finished. You unwrap the husk of the tamale like the tiny gift that it is. The masa is soft; the meat is tender and spicy.

I viewed my disdain toward cooking as an extension of hers. If she was miserable in the kitchen, then I would be, too.

I fell into cooking by way of tradition. I spread masa on husks because I was told to. When I was old enough to be enticed by rebellion, but still too young to care about things like heritage and culture, I stuck my nose up at anything culinary. Being in the kitchen meant either being of service to men or feeling inadequate because my skills did not yet match those of my elders. My one-time narrow understanding of cooking can probably be directly traced to all of those years making tamales. Witnessing my grandma wear her obligation like an ill-fitting coat, making dozens of tamales each Christmas (while the men got to sit around and crack jokes and drink beer) left a lasting impression on me. My grandmother’s resentment toward cooking was birthed from expectation. She did not have time for a thing like feminism. Grandma held little regard for her “place in the kitchen”; providing meals for the family was simply a responsibility, one she nearly left behind altogether once the children all grew up, and she became someone she felt she could stand up for. I viewed my disdain toward cooking as an extension of hers.

If she was miserable in the kitchen, then I would be, too.

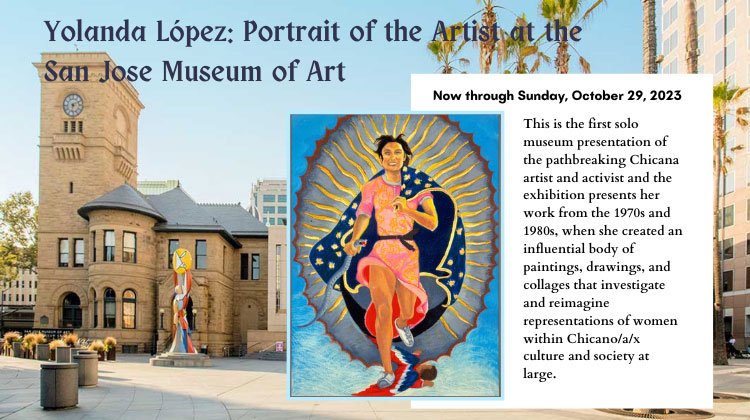

Examining Mexican feminism through the lens of food, cooking, and consumption is a scarce field of study. Some Mexican feminists believe that could be due to the fact that, historically speaking, the kitchen has been a place of banishment for women, especially in Mexican culture. Stripped of our uniqueness, we’re deemed good women (or “pure,” and in alignment with La Virgen) only to the degree that our food was considered acceptable by the men for whom we cooked. With that in mind, I sympathize with any desire to reject cooking altogether. For some women in our culture, there is nothing liberating about having an answer whenever someone asks, “What’s for dinner?”

My grandmother does not sit alone with her hostility. In “Cooking Lessons,” a short story by poet, author, and Mexican feminist Rosario Castellenos, an obligated woman attempts cooking a roast for her husband for the first (and probably last) time. As she tries to prepare the meal, the protagonist’s inner ramblings paint a picture of an educated, liberal woman who views domesticity as foreign and beneath her. “I wandered astray through classrooms, streets, offices, cafes, wasting my time on skills that now I must forget in order to acquire others. For example, choosing the menu. How could one carry out such an arduous task?” She interprets her role as housewife as troublesome; a sacrifice she must make for her less-than-satisfying marriage.

What I once dismissed as a mere gender expectation—particularly that of a ‘good Mexican woman’—I instead understood as something I deeply enjoyed.

Although it was not at all a deliberate or feminist decision on her part, I still view my grandmother as a challenger of the general voicelessness and passivity of so many women of her generation, especially other Mexican women. I saw my grandmother in Castellanos’ story—and for many years, I suppose I saw myself in it as well.

As I neared 30 years old, however, I began to question nearly everything that a person in their late 20s often does. I had a change of heart. What I once dismissed as a mere gender expectation—particularly that of a “good Mexican woman”—I instead understood as something I deeply enjoyed. Making the same dishes and recipes that the women in my family have made for years began to feel like a homecoming. I was, in some simple way, honoring them and their struggles—my grandma especially— and getting to know myself better, too. Cooking stopped being something I felt I should reject out of loyalty to my grandmother, or in the often problematic name of mainstream (white) feminism.